Polar Bear Day celebrates one of nature’s most impressive hunters, and the world’s largest carnivore. When fully grown, polar bears can span an enormous 9 feet (2.7m) in height.

Word of the Day

| |||

| Definition: | (adjective) Having soft nap produced by brushing. | ||

| Synonyms: | napped, brushed | ||

| Usage: | Though the train was unbearably cold, she snuggled into the fleecy lining of her coat and promptly fell asleep. | ||

Idiom of the Day

rarer than hens' teeth— Incredibly scarce or rare; extremely difficult or impossible to find. |

two gold cup winners!

History

Hugo LaFayette Black (1886)

| Black was a US Supreme Court Justice for 34 years. A prominent supporter of the New Deal, he was also in the majority that struck down mandatory school prayer and guaranteed the availability of legal counsel to suspected criminals. He was known for an absolutist belief in the Bill of Rights, and his last major opinion supported the right of The New York Times to publish the Pentagon Papers, which revealed improper government conduct. |

Shrove Monday

Many countries celebrate Shrove Monday as well as Shrove Tuesday, both days marking a time of preparation for Lent. It is often a day for eating pastry, as the butter and eggs in the house must all be used up before Lent. In Greece it is known as Clean Monday and is observed by holding picnics at which Lenten foods are served. In Iceland, the Monday before Lent is known as Bun Day. The significance of the name is twofold: it is a day for striking people on the buttocks with a stick before they get out of bed as well as a day for eating sweet buns with whipped cream.

What Would Life Be Like on the TRAPPIST-1 Planets?

The TRAPPIST-1 system is home to seven planets that are about the size of Earth and potentially just the right temperature to support life. So how would life on these alien worlds be different than life on Earth?READ MORE:

What Would Life Be Like on the TRAPPIST-1 Planets?

1827 - New Orleans held its first Mardi Gras celebration.

1867 - Dr. William G. Bonwill invented the dental mallet.

1883 - Oscar Hammerstein patented the first cigar-rolling machine.

1896 - The "Charlotte Observer" published a picture of an X-ray photograph made by Dr. H.L. Smith. The photograph showed a perfect picture of all the bones of a hand and a bullet that Smith had placed between the third and fourth fingers in the palm.

1922 - The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the 19th Amendment that guaranteed women the right to vote.

1963 - Mickey Mantle of NY Yankees signed a baseball contract worth $100,000.

1974 - "People" magazine was first issued by Time-Life (later known as Time-Warner).

1997 - Don Cornelius received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

1998 - Britain's House of Lords agreed to give a monarch's first-born daughter the same claim to the throne as any first-born son. This was the end to 1,000 years of male preference.

1999 - Colin Prescot and Andy Elson set a new hot air balloon endurance record when they had been aloft for 233 hours and 55 minutes. The two were in the process of trying to circumnavigate the Earth.

DAILY SQU-EEK

READERS INFO

FUN FACTS

1) At the encouragement of the U.S. State Department, Detroit, Michigan mayor Coleman Young awarded Saddam Hussein the symbolic key to the city of Detroit in 1980. This followed a string of events in which Reverend Jacob Yasso of the Chaldean Sacred Heart in Detroit publicly congratulated Saddam on his rise to power, resulting in Hussein donating $250,000 to Yasso’s church (and later $200,000 more). A year after this first donation, Yasso was invited as a guest of honor to Iraq and given “the key to Detroit” to give to Saddam on behalf of the mayor. The State Department, in this instance, was using the age-old “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” with regards to Saddam who at the time was waging a war against Iran, hence the United States’ desire to buddy up to the Iraqi leader.

2) In June of 1999 while out for his customary 4-mile walk, Stephen King was struck by a light blue 1985 Dodge Caravan being driven by 42 year old Bryan Smith who previously had “a dozen vehicle-related offences,” according to King. In this one, Smith claims he’d been distracted by his dog who had been trying to get at some meat in a cooler in the back seat. About a year and a half later, Smith was found dead in his home. A friend of his, John Thompson stated that after the ensuing legal issues, “Bryan had nothing left. He said to me, ‘I’d hate to go through another winter dragging my way up and down the highway in the snow.'” As for King, he was lucky to be alive. One of the paramedic’s who responded to the scene stated, “I’ve been doing this for 20 years and when I saw the way [King was] lying in the ditch, plus the extent of the impact injuries, I didn’t think [he’d] make it to the hospital.” King suffered, among other things, a acetabular cup fracture of the right hip, shattered leg and knee, laceration to the scalp, chipped spine (in eight places), and collapsed lung. Shortly before Smith’s suicide, King also bought the damaging Dodge for $1,500. His plans for the automobile were to “take a sledgehammer and beat it!”

3) According to the BBC, a Swedish woman named Lena Paahlsson lost her engagement ring while doing some Christmas baking with her daughters back in 1995. Sixteen years later (2011) and after Mrs. Paahlsson had lost any hope of finding the ring, she was pulling up carrots in her garden when she amazingly found her ring with a carrot growing through it. Her theory on how it got out there was that it must have fallen in the sink when she’d been peeling vegetables. She then would have used the peelings to either feed her sheep or as compost. Either way, it ultimately ended up in her garden and, sixteen years later, on a carrot.

4: “School” comes from the Ancient Greek “skhole”, which meant “leisure or spare time”.

5: A “tittle” is nothing dirty, it’s simply the name for the dot over the letter “i”

can you help me, Mr?

Pictures of the day

Ellen Terry (1847–1928) was an English actress who became the leading Shakespearean actress in Britain. Born into a family of actors, she began performing as a child and toured widely in Britain in her teens. Among other comic and dramatic roles, she gained fame for her portrayals of Portia in The Merchant of Venice and Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing, opposite Henry Irving, both in Britain and America. She later managed the Imperial Theatre in London, lectured, and continued to act until 1922.

CHEESE AND SAUSAGE ARE WHAT

SIBERIAN JAYS LIKE!

– so Edwin discovered on a skiing holiday with his family in northern Sweden. Whenever they stopped for lunch, he would photograph the birds that gathered in hope of scraps. On this occasion, while his family ate their sandwiches, Edwin dug a pit in the snow deep enough to climb into. He scattered tidbits of food around the edge and then waited. To his delight, the jays flew right over him, allowing him to photograph them from below and capture the full rusty colors of their undersides more clearly than he had dared hope.

thanks, Sally

One Row Lace Scarf pattern by Turvid

knit

knit

knit

knit

thanks, Shelley

crochet

thanks, Nicki

crochet

crochet

crochet

thanks, Shelley

Goulash Recipe

Touchdown Butterscotch Dip

gooseberrypatch

2 11-oz. pkgs. butterscotch chips

5-oz. can evaporated milk

2/3 c. chopped pecans

Optional: 1 T. rum extract

apple and pear wedges

Combine butterscotch chips and evaporated milk in a slow cooker. Cover and cook on low setting for 45 to 50 minutes, or until chips are softened; stir until smooth. Stir in pecans and extract, if using. Serve warm with fruit. Makes about 3 cups.

5-oz. can evaporated milk

2/3 c. chopped pecans

Optional: 1 T. rum extract

apple and pear wedges

Combine butterscotch chips and evaporated milk in a slow cooker. Cover and cook on low setting for 45 to 50 minutes, or until chips are softened; stir until smooth. Stir in pecans and extract, if using. Serve warm with fruit. Makes about 3 cups.

Make your own mod podge at a fraction of the cost!

Preview by Yahoo

| |||||

Banana Inflorescence Jigsaw Puzzle

WORD SEARCH

| board bucolic census check citizen curriculum cycle daring | ecumenical enumerate favor forged heart heroic | match mentor myriad offset process pylon | rage realm region route rural ruts salve score seep state | thwart unite untold yokel |

Adam Pizurny

QUOTE

CLEVER

Crystallized Honey? No Problem!

Fun fact! Honey has an eternal shelf-life, which means – you could store it in your pantry for years on end! But if you find that your honey has gone into a crystallized state, you can get it back to its liquid form by removing the lid and placing it in the microwave on 50% power for two minutes.

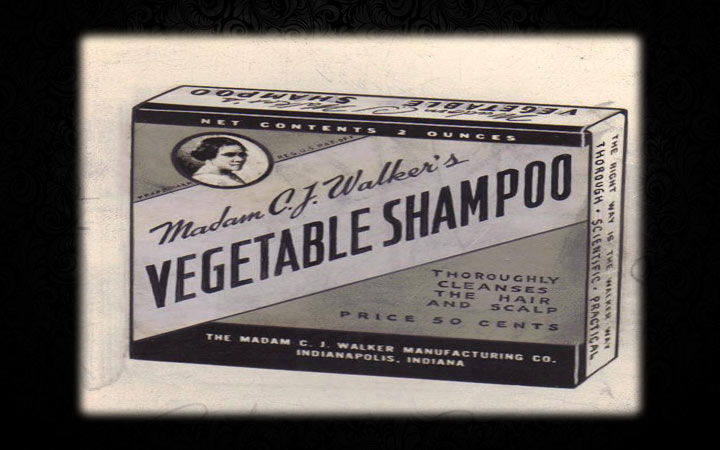

The History of Shampoo

randomhistory

A Culmination of Personal Cleanliness

In modern society, the practice of good personal hygiene is usually a minimum expectation instilled within children from the earliest possible moment. Most civilized societies demand it, even take it for granted. But the history of shampoo, or the product used specifically for shampooing of the hair, is confined to about a century of very recent development. Before innovations in shampooing, the hair was maintained with a combination of soap, perfumes, and essential oils, none of which provided the quality of cleanliness and luster of a modern shampoo, because it took innovations in modern science to truly understand the composition of hair soil in order to develop cleansing formulas to combat it. The history of human hygiene, however, emerges with the dawn of civilization, when humans perceived themselves as distinctly different from other creatures. In a way, the science of shampoo is one among many milestones of achievement in personal hygiene, a pinnacle of cleanliness.

A General History of Personal Cleanliness

In the “bursts” of human development beginning about 5000 B.C., early civilization began to arrange itself around agricultural and urban centers. By as early as 4000 B.C., Virginia Smith suggests, a cosmetic routine emerged during the Eurasian Bronze Age wherein beauty was managed through a system of pampering, from bathhouses to hairstyling. Smith identifies her “history of clean” as one of ellu, the “ancient Mesopotamian word meaning a type of glittering, strikingly luminescent, or beautiful cleanliness” (2007). But while surely most of the pampering rituals were reserved solely for the upper echelon of society (something which remained true throughout much of history), the broad acceptance of personal cleanliness had “become an established feature of society” by about 3000 B.C., because the emerging sense of human society came to believe that “the extra ‘polish’ or ‘finish’ given by their grooming and adornments separated them from all other animals” (ibid).

In the ancient world, Egypt was the center of a thriving cosmetic trade, and early cosmetic scientists learned to exploit virtually every known natural resource for its purpose, from local raw materials to harvested domesticated products, such as lotus flowers for essential oils. Like today, the ancient cosmetic toilette used pumice stone as an exfoliator, “and the natural sponges found in warm seas [were] used for sluicing the body” (Smith 2007). Beauty was itself a deeply revered attribute. The ancient Greek word kosmos meant “to order, to arrange, or to adorn” while its derivative, the antecedent to the English “cosmetics,” was kosmetikos, which meant “having the power to beautify” and was a quality attributed of the high priestess who maintained the beauty of the temple.

The beauty ritual was also prominent in the Babylonian courts in the third millennium B.C., where archaeological evidence of a palace shows multiple bathrooms complete with clean, running water. In addition, evidence of soap said to have been made from animal fats boiled with ashes has been found in clay jars, though it is unclear precisely what the soap was used for (Naiman 2004). Evidence of more widespread personal hygiene can be found later in the classical Greek period. The Greek emphasis on the purity of clean water and personal cleanliness would be further standardized by the Romans, whose bathhouses and aqueducts remain famous examples of technological innovation in the ancient word designed to improve the quality of life, perhaps most importantly for reasons related to one’s personal health, hygiene, and cosmetic appearance.

Bathers still commonly used abrasive surfaces such as pumice to scrape away soil, and they followed that with perfumed oils and lotions, though recommendations by the second-century physician Galen in such texts as De Sanitate Tuenda (“On the Healthy Life”) began pointing to soap products as beneficial to personal hygiene (Smith 2007). But even among royalty, where hair was styled and perfumed, if soap was used in the hair it could not have impressed its users. Besides being irritating to the eyes, most standard soap was ineffective in properly cleansing the hair. Soap was difficult to wash out and left behind a dull film. Good shampoo, let alone the word itself, was still centuries away.

From popular culture, it is easy to dismiss the concept of personal cleanliness in the Middle Ages. Indeed, Virginia Smith identifies an ascetic basis for the era following the fall of the Roman Empire that suggests a reason for such a belief: the Judeo-Christian ethic emphasized the purity of the soul and, hence, inner cleanliness took a privileged position over the outer body. But even as waterways such as the Roman aqueducts were either destroyed in war or fell into disrepair, communal bathhouses remained a vestige of many urban centers throughout the Middle Ages, despite the long-standing edict of A.D. 745 by Pope Boniface that forbade unisex bathing facilities. Eventually, however, as bathhouses became houses of ill-repute in growing urban centers and as disease, particularly syphilis, became widespread (largely related to the bawdy undercurrent of the public bathhouse), most closed with approval from religious leaders in the constantly changing political climate.

It seems clear, though, that where opportunity for maintaining one’s personal cleanliness existed, people took advantage of it. In some circumstances, however, opportunities for accomplishing one’s personal cleanliness may have been fewer, and activities such as delousing one’s hair may have been one of the few still-available practices. Nevertheless, the “countdown to modernity” that began in the seventeenth century had begun, and gradually the present-day hallmarks of “safe, convenient, and civil methods” of personal hygiene began to emerge (Smith 2007).

The Therapeutic Massage of Dean Mahomet

Bathhouses had made their triumphant return long before Dean Mahomet arrived in London. A native of the Bengal region of India under the rule of the English East India Company, Mahomet entered into the service of the English Company’s army at an early age before going on to travel in Ireland and England. Mahomet documented his journey in his Travels, the first book written in English by an Indian. Published in 1794, Travels was an epistolary text, or a series of letters supposedly composed to a friend during his time abroad. In one letter, Mahomet acquaints his reader with the technique of Indian therapeutic massage that includes “the practice of champing, which is derived from the Chinese.” Mahomet quotes from “the ancients,” that a “female masseuse/shampooer, with her agile art, runs over his body and spreads her skilled hands over all his limbs.” In other words, a relative to modern massage therapy, the shampooer “rubs [the client’s] limbs, and cracks the joints of the wrist and fingers…[which] supples the joints, but procures a brisker circulation to the fluids apt to stagnate, or loiter through the veins, from the heat of the climate” (Mahomet 1997).

Upon arriving in London, Mahomet’s initial work was with the Honorable Basil Cochrane, who claimed to have drawn upon British inspiration to devise a kind of vapor bath cure (something in practice in Britain’s Indian colony) for use in improving the general health of lower-class Londoners. After a while, Mahomet accumulated some wealth and opened up his own Indian-style public eating house. When he was forced to sell his interest in the shop, Mahomet returned to the bathhouses and, though in many cultures washer people are among the lowest classes, Mahomet battled against type and the constraints of the alien culture and rose to the challenge of carving out an identify for himself. Mahomet implemented Indian shampooing methods he had practiced under Cochrane and, alongside the traditionally vapor bath, he employed a broad range of new treatments that helped him become the preeminent practitioner of his trade, eventually becoming the “shampooing surgeon” to royalty (Mahomet 1997).

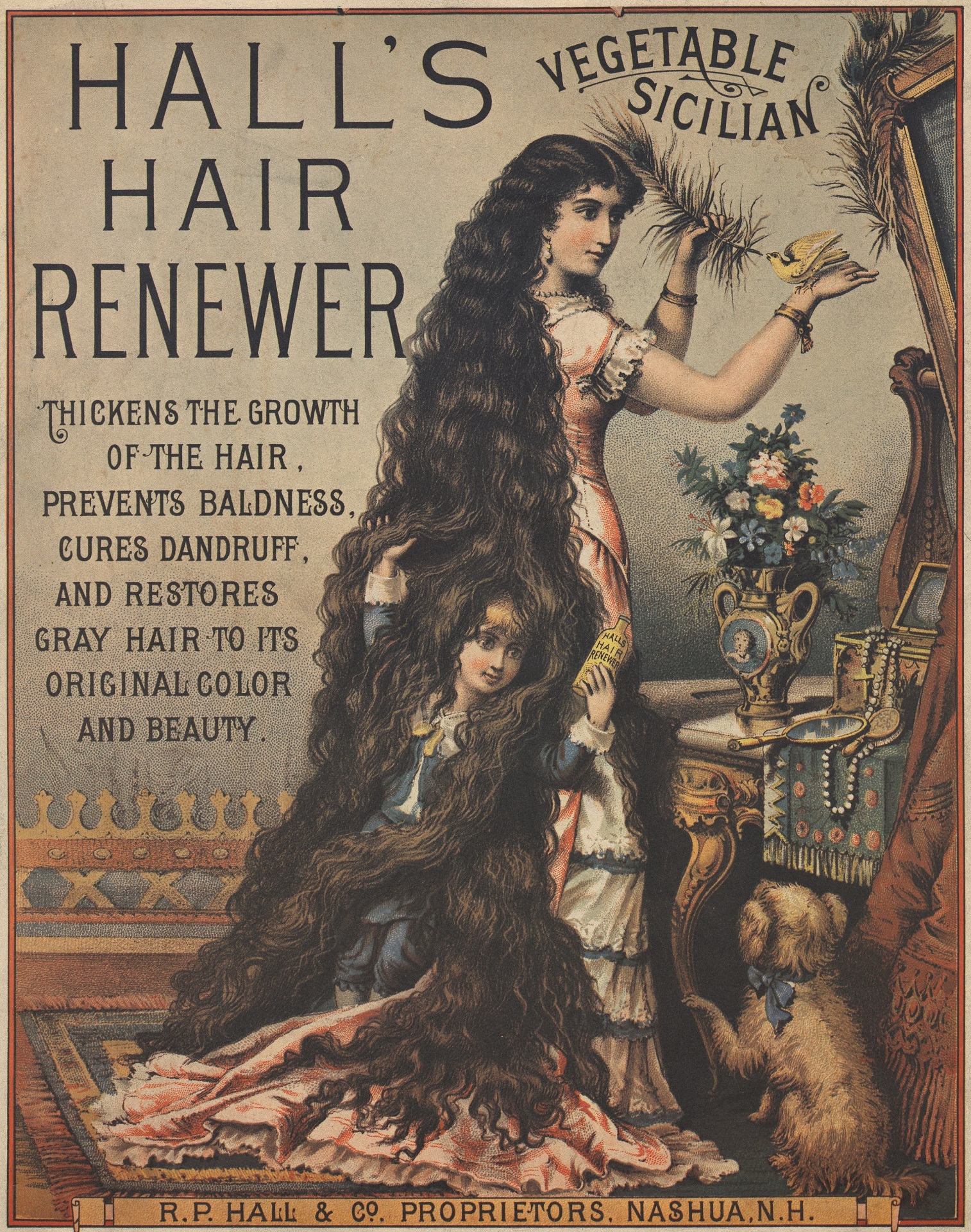

The practice of shampooing (from the Hindi champi) via the Chinese was popular among the colonizing English in India, so it translated well to London, if only because the description portrayed young, skillful women practitioners with “long fingers, and a satined skin.” Ultimately, however, it was the “idea of shampooing for health” that made the practice so popular in medical circles, where the concept got taken up and redeployed for other uses within a few decades (Mahomet 1997). But soon the word “shampoo” was used specifically to describe hair and scalp massaging products, often made from soap boiled in soda water and mixed with herbs for fragrance and health benefits. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the term “shampoo” was first recorded with respect to the meaning “to wash one’s hair” in 1860 and as a noun meaning “the soap used for shampooing the hair” a few years later, in 1866. But hair care was still an uncomfortable burden, particularly for those with heavier, longer hair. Luckily for them, chemists began experimenting with solutions to this problem. Indeed, shampoo would become the realm of science, when the problem could be understood at a chemical level and the proper formulas could be developed to address the problem.

Innovation in Hair Care

At the turn of the century, when hair care was still a deeply troublesome practice, the industry was poised for a breakthrough. In 1898, the Berlin chemist Hans Schwarzkopf opened a drugstore with a section dedicated to perfume. When that part of his business proved especially successful, the chemist focused his efforts on developing new products for it--most importantly, products for the hair. According to the current company’s Web site, “Hans dislike[d] the expensive oils and harsh soaps used to wash hair, and [was] inspired to create a better solution.” What Schwarzkopf developed was a water-soluble powder shampoo. It’s ease of use made the product so popular that by the next year Schwarzkopf began to supply his powder shampoo to virtually every drugstore in Berlin—and with an eye on the international market (Schwarzkopf-professional.com). Despite the powdered shampoo’s convenience, the soap products it still contained caused undesirable alkaline reactions that dulled the hair.

An article published in the New York Times in May 1908 outlines a number of “simple rules” on “How to Shampoo the Hair.” It is aimed specifically at women, claiming that “every woman likes to have her hair not only daintily and becomingly arranged, but soft and glossy in appearance and texture…[and] the shampoo is a necessary part of the treatment,” whether the feat is to be achieved by oneself or with the help of “one’s maid or hairdresser.” The article explains hair is best shampooed at night, following a thorough combing and brushing of the hair, and then carefully singeing all split ends. After an olive oil-based Castile soap is applied with a stiff brush, the hair is rinsed four times, the latter rinses with cooler water to prevent the head from overheating and limit the potential for catching a cold. If it sounds like a difficult regimen to follow, it should be noted that in 1908, many “hair specialists recommend the shampooing of the hair as often as every two weeks, but from a month to six weeks should be a better interval if the hair is in fairly good condition” (emphasis added). In other words, the gradual build up of soils both natural and from the environment over the course of two or more weeks clearly necessitates the ritual, if only because less demanding hair care products were only just emerging.

Indeed, the same year as the article hit newsstands, Dr. John Breck introduced one of the first shampoos to America before going on to develop one of the world’s first pH-balanced shampoos in 1930. Under Breck’s reign, the business and products remained local, known only to his native New England. His son Edward took over management of the company in 1936 and soon partnered with illustrator Charles Sheldon, the artist responsible for creating the first pastel portraits of “Breck girls.” The campaign would become one of the longest running in American history as Sheldon created 107 total oil and pastel portraits, including that of seventeen-year old Roma Whitney, whose profile would become the registered trademark of the company in 1951. Additional portraits were created by Sheldon’s successor, Ralph William Williams, who employed professional models and helped lift the company to the peak of its success in the 1960s (Minnick 1998).

Meanwhile, Hans Schwarzkopf continued to innovate in Europe, and in 1927 he not only introduced one of the world’s premiere liquid shampoos but also launched his international empire of hairdressing technique institutes. Descendant lines of the Schwarzkopf Institute for Hair Hygiene remain active around the world today, implementing new products and continually innovating in the industry of hair care, from the first nonalkaline shampoo in 1933 to perms, hair sprays, and mousses. In 1980, the company led the way in a major environmental concern by converting to CFC-free aerosol spray cans (Schwarzkopf-professional.com). Today it operates under the name of “Schwarzkopft and Henkel” and is headquartered in Düsseldorf, Germany. The Henkel brand is well known in the United States, responsible for such major brands as Dial and Right Guard. The worldwide network remains strong, and the company remains a leader in hair care innovation, the science of which continues to develop with our understanding of the science of hair itself.

The Science of Shampoo

The hair-specific composition of shampoo products is designed for the individual’s desire to practice both good personal hygiene as well as the “cosmetic ritual that addresses a concern for appearance” (Wong 1997). The proper cleansing of hair must address the complexity of soil that builds up from a combination of airborne contaminants, hair care products and, most importantly, oily hair lipid and sebum secreted by glands in the skin. When this natural byproduct combines with external pollutants, they build up on the individual follicles of hair and the hair takes on an oily, slick appearance. The innovations in hair care in the past one hundred years focus on this issue by using materials that target the hair lipids through “highly surface-active” cleansing agents called surfactants to break down and distribute healthy natural oils while washing away contaminants (Wong 1997).

The composition of shampoo has been developed and marketed to specific types of hair since the early nineteenth century, but modern shampoos have achieved a pinnacle of performance and specificity. Though the primary attribute of a good shampoo is effective cleansing of the hair, shampoo manufacturers must address a wide array of needs, from conditioning and anti-dandruff formulas to specially styled and color-treated hair. There are also milder shampoos for babies and shampoos containing natural, often plant-derived ingredients to replace harsher chemicals (Wong 1997). Shampoo may be a late entry in the arena of personal hygiene, but our knowledge of cleanliness is one that remains under intense scrutiny by scientists as we adapt to battle the ever-changing world of dirt and filth—a world that is now understood microscopically.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment